Entry #22: de-LuLu

Tender Trap Trilogy 1- de-Lulu

🀄️A mahjong table, a Cantonese punchline, and the moment Lulu stops being a joke and becomes a person again 🧧

It’s the first day of the Lunar New Year. I wake up to the sound of firecrackers and the smell of incense. I slip into a brand new red cheongsam, and feel the weight of the year of the Fire Horse resetting. The first angpao comes from my mum, her nails still perfect from yesterday’s salon visit, her smile already planning the next round of gossip.

As I sip my coffee, my mind drifts back to last night’s reunion dinner, the most important meal in our calendar, the one where every story, triumph, and failure gets retold under the same roof.

After dinner the tables were cleared, the tiles came out, and the sound of mahjong filled the house like rain on a tin roof.

That’s when I heard it, from the corner where my aunties and uncles were playing, voices sharp with laughter and mock outrage:

「你咪當我係Lulu喎!!!!…」

Everyone roared. Someone slapped the table, coins clattered. The phrase still has bite after all these years, those 8 Cantonese characters that shift from “don’t take me for a fool” to “don’t you dare underestimate me,” depending on how you tilt your head when you say it.

I was born and raised in Malaysia, but Cantonese is my mother tongue. For families like mine, Malaysian Chinese who grew up under ceiling fans and Hong Kong reruns, TVB was practically family. Those dramas weren’t background noise. They shaped how we joked, argued, flirted, even scolded our kids. Hong Kong slang travelled south through the airwaves and picked up new accents in Kuala Lumpur, Penang, and Ipoh. 你當我係 Lulu 啊? became ours too, same phrase, different melody.

If you don’t speak Cantonese, you’ll miss the sting. The English version sounds almost like a bad sitcom title. In Cantonese it hits differently, depending on tone, facial expression, and the body language.

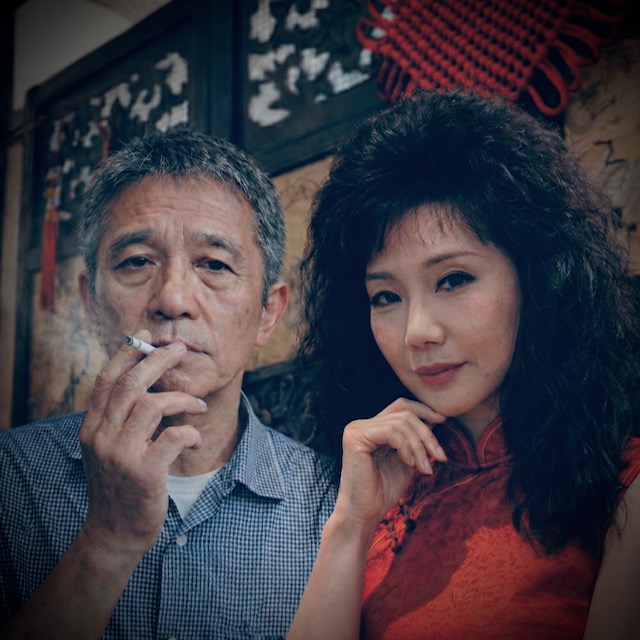

The first Lulu I ever saw wasn’t real. She lived inside our wood-panel television between static and cigarette smoke. My mother sat on her favourite sofa, one hand chasing cold cha siu rice with chopsticks, the other holding a takeaway box. I pretended to do homework but mostly watched her watching them.

There were heroines who suffered beautifully. And then there were archetypes everyone recognised instantly. The pretty gold-digger with no backstory. The voice pitched just a little too sweet. 嗲聲嗲氣. Not apologising for existing, just playing a type so obvious it became shorthand for foolishness. Names that sounded Western without quite arriving. Candy. Mimi. Lulu.

Sometimes Lulu wasn’t even a character. Just a nightclub hostess with two lines, hair so big it probably needed its own bottle of hairspray, bracelets clinking louder than her dialogue. Completely one-dimensional, there to signal rather than live a story.

They were often played by actresses who never quite made it to star status, handed roles that stayed flat on purpose. The stiffness, the slightly awkward delivery, almost suited the character. Lulu wasn’t meant to grow. She was meant to appear, sparkle for a moment, and disappear.

What made her Lulu wasn’t stupidity. It was wanting something so badly she pretended not to see the exit signs. You’d watch her chase promises that were never going to arrive.

Looking back now, the acting feels almost theatrical. Sets that looked like they might collapse if anyone slammed a door, hairstyles that defied gravity. And yet those images stayed with us. Lulu became a cultural shorthand we carried into adulthood, half joke, half cautionary tale.

Years later, watching stories that revisited those same archetypes felt different. In Tony Ayres’ film The Home Song Stories, adapted from his memoir, the figure that once looked like a stereotype softened into memory, shaped by a son trying to understand a complicated mother rather than reduce her to a joke. That shift stayed with me. It made me realise how easily a punchline can turn back into a person.

Real women never moved like TVB extras at all. They laughed louder, worked harder, aged in ways the camera never allowed. Under neon lights in different cities, I began to see versions of Lulu that were not flat at all. Women who understood the room faster than anyone else. Women who could turn a glance into survival. Women who knew exactly what people thought of them and carried on anyway.

And Lulu was always there, in sequins that caught too much light, negotiating from the wrong end of power, teaching me things no one ever said out loud. Not because she had power, but because she showed how a role can become armour if you know when to step out of it.

At some point I started to notice how the phrase followed me too.

Some people approach life with small detours. Gentle invitations that feel new each time they are offered. I did not recognise the pattern the first few times either. One message arrived while I was paying for groceries. I stared at it longer than I want to admit before laughing at myself.

Different words, same question mark.

I used to say yes. Not because I did not know better, but because I wanted to be seen as kind, generous, not just business. That is the little trap. If you draw boundaries you seem too composed, too clever, and suddenly it kills the sexiness. If you do not, the hours stretches longer than it should.

What Lulu had not learned yet, and what took me years to understand, is that some evenings arrive already half written. I remember discreetly checking the clock on my wall while someone described how he imagined the session unfolding, nodding because the moment felt warm and familiar.

He left smiling. I stayed where I was and the session still ended exactly on time.

Sometimes we both know the scene and still enjoy pretending we do not. The performance is not the problem. Forgetting that part is.

When someone says, “You’re not like the others,” I hear it as curiosity more than comparison. I smile, let the moment stay light, give enough warmth for the memory, and still end on schedule. Because the real point of not being Lulu is not winning the scene. It is knowing when to call cut, and still smiling.

Maybe we all carry some version of her, half sketch and half projection, until we learn which lines are ours to redraw.

Later that night, after the visiting and the laughter fade, I hang the blue cheongsam back in my wardrobe. The silk is warm from last night’s noise, from aunties arguing over tiles, from a language that knows how to joke without cruelty. For a moment I hear the old studio audiences in my head, applause drifting through memory like distant fireworks.

「你咪當我係Lulu喎。」

This time the phrase lands differently. Not a warning. Not a punchline. Just a quiet smile.

No. I just know exactly why you asked.

Leave a Comment