Entry #20: Suzie Wrong

🍵 I forgot I have a cheongsam tucked somewhere in my wardrobe. Now I want to run home and wear it again. 🏃🏻♀️

Chapter 1

I was sitting in a café in Surry Hills, nursing an overpriced matcha and thinking about nothing, when the older man at the next table leaned in with a cheeky grin and said:

“Excuse me, love… you look just like Suzie Wong. Where are you from?”

For a split second I thought I misheard him. I thought he said Penny Wong.

Then he said it again, slower, like he was doing me a favour.

“Suzie Wong. From the movie.”

Ah.

The name rang a faint bell. Not a clear memory, more like the outline of something you have heard referenced your whole life, the way certain old film titles just hover in the air. I must have looked blank because he brightened immediately, delighted to have found a doorway.

“You haven’t seen it?” he asked, almost offended on behalf of his own youth. “Love story. Hong Kong. Bhiutifulll !!!!…”

I laughed. His certainty was so pure.

He introduced himself as Bill, and the conversation did what café conversations do. One comment becomes a story. A story becomes a decade. Suddenly we were no longer two strangers beside a matcha and a coffee. We were in a small pocket of time that belonged to him.

He told me he watched The World of Suzie Wong when he was young, and he said it the way men say “the first car I drove” or “the first woman who wrecked me.” Tender, proud, slightly embarrassed, and completely certain it mattered.

“You know where I saw it?” he said, leaning in.

I assumed he meant an old cinema in Sydney.

“No,” he said, and grinned. “Vietnam.”

That surprised me, and it must have shown, because he rushed to place the memory properly, as if it still needed to be filed correctly. 19 or 20 years old maybe? One of the Australian boys. In late 1960’s, maybe early 1970’s. He was not giving me a history lesson. He was showing me where the movie lived in him.

Chapter 2

They screened films on base sometimes. A sheet for a screen. A projector doing its best. A couple of hours where young men could stop being soldiers and turn back into boys. He described it with this matter of fact warmth, like of course you would want a love story in the middle of a war. Of course you would want colour and music and a woman you could hold in your mind when everything else was mud and heat.

“We’d been out all day,” he said. “Hot, wet, BO, yuck! Then someone puts on this movie. And suddenly it’s Hong Kong. Neon lights. Harbour. Music. This hot bird, Suzie.”

He said it like he could still see her.

“And she wasn’t some innocent little thing,” he added quickly. “She was cheeky. Worked in a bar. Trouble. But not dumb trouble.”

Bill told the plot in affectionate shorthand, the way people do when they remember scenes, not summaries.

“This western bloke, comes to Hong Kong thinking he’s going to reinvent himself. And he meets her. She plays at being a rich girl, then you find out she’s… you know. She works…”. He paused, then winked.

“She wanted out,” he said. “She wanted love. She wanted someone to pick her.”

Then he laughed at himself. “Jesus, it sounds corny doesn’t it?.”

It did not sound corny. It sounded familiar. That is the shape of the story men keep. The “good prostitute”. The exception. The woman who sells sex but secretly wants to be rescued by the right man. The fantasy with a moral halo.

Bill did not use those words. He just told me what the film did to him and his mates.

“We all loved it,” he said. “Because it made Hong Kong look like a dream. Like you could step off a plane and the whole world would be… colour. And girls like that. Everywhere.”

He said “girls like that” the way men do when they mean a type, not a person.

Then, like it was the sequel, he told me what happened next.

Chapter 3

They got leave, and suddenly the map got bigger. Hong Kong, Thailand… Anywhere warm and bright and slightly unreal from the other side of a war. Bill talked about Wan Chai and bar streets and neon that made everything look softer than it was. He and his mates, twenty year olds playing adult, walking shoulder to shoulder like they had invented appetite. And everywhere, the same image the film had fed them: Western men with small Asian women in tight dresses, walking like they belonged to each other.

“And we used to call them Suzie Wongs,” he said, almost sheepish now. “Not nasty. Just what we called it. Everyone did.”

He said it like someone confessing an old habit.

“Wan Chai was mad”, he said. “sticky tables, loud music, a few cold ones in hand, you na…and these hot birds in those Chinese dresses! They knew exactly what they were doing to a bunch of 20-year old idiots!”. He laughed.

That is when an ancient Chinese line floated up in my head. Not as a warning exactly. More like a caption that fit his story too perfectly.

Chapter 4

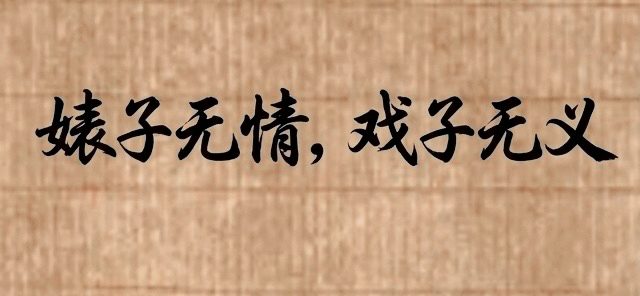

I let him finish, then said, “We actually have a line for this in Chinese. It’s brutal, but it’s oddly accurate.” I murmured in Cantonese:

“婊子无情 ,戏子无义”

And because his face went blank, I gave him the straight version.

Prostitutes: “no feelings.”

Actors: “no loyalty.’”

In other words: don’t trust either of them.”

His eyebrows rose. “Bloody hell,” he said, with the pleased shock of a man who loves a sharp proverb.

It sounds like it is judging two professions. But really, it is describing the people who need those professions to be fake.

Bill heard it as a warning label. I heard it as the missing subtitle to his love story.

People reach for sayings like this because they are convenient. They let you enjoy the intimacy, enjoy the romance, enjoy the dramas and still walk away clean. It’s a loophole.

婊子无情 “Prostitutes have no feelings” is not really the problem. The fear is that she can turn the feelings on and off. That means she is not swept away. She is not helpless. She is not yours. And yet the same men will ask you to remember their birthday, to listen properly, to care. Then they flinch when the prostitutes might actually mean it.

Chapter 5

Bill’s movie is built on the fantasy that the prostitute is secretly pure, secretly loyal, secretly just waiting for the right man to choose her.

And that Chinese idiom is built on the opposite fantasy. That she cannot be loyal at all, and that the performer cannot be sincere.

Different morals. Identical hunger.

The film says: she is redeemable if she suffers and if a man chooses her.

The idiom says: she is not redeemable, so do not get sentimental.

Same outcome.

Either way, she becomes a lesson for someone else. Not a person.

Chapter 6

Bill gulped his water next to an empty coffee cup, and glanced at his watch for a second, like he was seeing his own memory differently.

“You know what’s funny,” he said. “Back then we didn’t think about any of this. We just watched. We wanted to see hot birds.”

“Yes,” I said. “That’s why it worked.”

People carry old stories around like loose change. They reach for them out of habit, not harm. But habit still shapes what they see.

Before he left, Bill mentioned a place in Crows Nest, something like Dragon Inn or Lucky Star, where the roast duck tasted like the Hong Kong he’d been chasing ever since.

Then he stood up slowly and put on his hat. He was dressed the old-money way, neat but not trying too hard. Shirt tucked in properly. Shoes that had seen polish. A handkerchief folded with care. And, sticking up from his back pocket like a quiet little antenna, a comb.

“You are a real stunner, love” he said.

Then, like he had earned the right to refine it, he added, “and you look like Suzie Wong, love.”

This time it sounded less like a verdict and more like a delighted concession. Like he had come in with one old story and left with a slightly better one.

I smiled back, because he meant it kindly, and because there are moments where correcting someone would be less intelligent than letting him leave with his dignity intact.

“Awww…thanks dahhring,” I said. “Nice to meet you, safe trip home, and happy Austraya Day!”, I winkend.😉

He shuffled out humming something from his youth, probably a tune from a film soundtrack. I pulled out my compact mirror. The eyeliner? The posture? Or just a woman willing to listen to an old war story over matcha?

I finished my drink, amused.

Chapter 7

Suzie Wong.

A movie that taught a generation of men how to romanticise a woman they did not have to fully respect.

“婊子无情, 戏子无义”

And a Chinese idiom that taught a generation of people how to deny the same woman moral character while still expecting her loyalty.

Suzie Wrong, indeed.

Not because Bill was malicious. He was nostalgic. He was human.

And because if there is one thing both the film and the idiom accidentally reveal, it is this: people do not just want a story. They want the story to belong to them.

They want it to feel personal, even when it’s performed.

They want it to feel priceless, even when it’s part of the deal.

It is a sweet kind of greed, really. A childlike one.

And watching Bill walk out humming, there was nothing sharp in what I felt. Just this:

What a strange, theatrical species we are.

💅🏼💅🏼 Me: The cheongsam’s back. So is my bad influence😜

💅🏼💅🏼 Me: The cheongsam’s back. So is my bad influence😜

Chapter 8 (Finale)

Watch“The Suzie Right” – the film Bill was talking about – here👆🏼.

Me? Im watching the other Wong:

Wong Kar-Wai’s In the Mood For Love.

Al Terrego

As good as it gets for long-weekend reading. You keep surprising.